We’re storing ever more information online so it pays to know what happens to your online accounts when you die. We investigate what the law says and the policies of the major players, before suggesting how to make sure your wishes are met. It might be something that many of us prefer to keep at the back of our minds, but there are times when we need to give some thought to what happens after we die. Even when we do consider our mortality, though, the fate of our online property is something that often gets overlooked. Much of this property has sentimental value – for example email folders, photographs and documents stored in the cloud, and our presence on social media sites – but it can also have financial value. It is likely that your Google account holds the keys to everything from your bank details to an archive of your career. (Also see: How to switch off notifications in Facebook Messenger.) Just recently it was reported by TechnoBuffalo that Apple was refusing to give a widow her dead husband’s password, and it was only after she went to the media that Apple issued an apology and offered assistance. In this instance it wasn’t that she wanted to retrieve data, but merely wanted to be able to continue using the iPad they had shared. Apple was just following company policy, but short of sharing all your sensitive passwords with family members, there must be a better way to manage a loved one’s online accounts following their death. Either way, you probably don’t want it to evaporate. You might also want to disable or deactivate an account to prevent, say, people making unwanted posts on a Facebook wall. Yet succession law is somewhat vague about some types of online property with the result that, unless you’ve shared your passwords, your relatives or the beneficiaries in your will may be unable to inherit it. Here we look at what UK law says about the subject, at how the big companies who administer our online assets interpret that law, and at what you can do to ensure that your wishes are met. (See also: How to fix WhatsApp: What to do when you can’t connect to WhatsApp.)

What happens to your Facebook account when you die

Facebook seems to take this issue seriously, and has an established policy in the UK that allows the executor of a will to request that an account is shut down or memorialised. Facebook retains the information, however, and you don’t get to see any information you wouldn’t have been able to see when the account holder was alive. Facebook is currently trialing in the US a feature that allows users to select what happens to their account after their death. (See also: What is Facebook Privacy Basics?) We asked Facebook about what happens to the online presence when the account holder dies and were told that two options are available in the UK, currently. Either the account can be deleted or it can be ‘memorialised’. Here is Facebook’s description of this latter option. “In the memorialised state, sensitive information such as status updates and contact information is removed from the profile, while privacy settings on the account are changed so that only confirmed, existing friends can see the profile or locate it in Facebook’s internal search engine. “The wall remains so friends and family – who are already friends with the profile – can leave posts in remembrance. When memorialised, no one can log in to the profile.” Needless to say, deletion or memorialisation both require proof of death and can be requested only by someone who can prove that they have authority to act on behalf of the deceased.

Even if the account is deleted Facebook maintains an archive of every account which contains a copy of everything that has ever been uploaded to it. The account holder is able to download this archive so we asked what the procedure was for a relative or someone holding a grant of probate to access the archive. We were told that this isn’t possible because it would represent a breach of privacy. While Facebook allows verified relatives to memorialise the account, they can only see information that the deceased had chosen to share with them. Facebook said it would not be appropriate to enable them to download that person’s private messages once they are deceased because no permission had been given. The company would not tell us whether they would respect someone’s wishes had they bequeathed their online assets in their will. There is every indication that this isn’t just rhetoric and that Facebook takes the issue of the privacy of deceased account holders very seriously. In a high profile case a few months ago, the parents of a 15-year-old who had committed suicide had hoped that by accessing their son’s Facebook account they would be able understand better why he had taken his life. Yet, Facebook fought all attempts by the parents to gain access, even after they had obtained a court order. This may be about the change, however. Facebook is now allowing US users to select in advance who controls their account when they die, and the service will eventually roll out elsewhere. After Facebook has received notice of your death, a specified ‘legacy contact’ can update your profile photo, accept friend requests and pin notices on your timeline. (See also: How to unsubscribe from LinkedIn emails.)

What happens to your Twitter account when you die

Like Facebook, Twitter has a policy that allows your executor or a family member to have your account deactivated. But it won’t allow that person access to your account, and it retains all the information. In response to similar queries to Twitter we were told that, in the event of the death of a Twitter user, the company can work with a person authorised to act on the behalf of the estate, or with a verified immediate family member of the deceased, to have an account deactivated. However, Twitter’s policy relating to providing access to an account following the death of the account holder is very similar to that of Facebook. “We are clear that Twitter users own their accounts”, the company told us. “For privacy reasons we are not able to provide access to a deceased user’s account regardless of their relationship to the deceased.” Again, the company was not forthcoming when we asked if it would permit such access in the event that provision was made in a will for someone to inherit online assets. However, the point was made that, unlike other services, much of the information on Twitter is public, so it is visible to anyone. (See also: 15 great Twitter tips and tricks.)

What happens to your Google account when you die

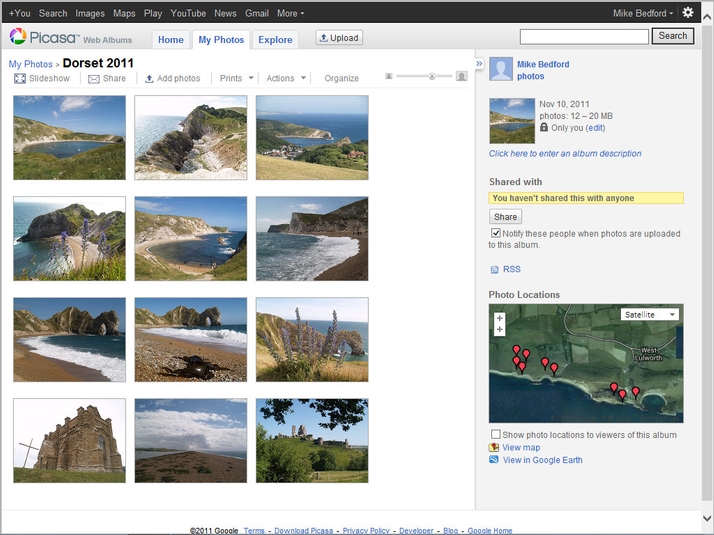

Google may be the most important account to access after a loved-one dies: unfortunately, it is also the least straightforward. Google deals with each case individually, and always retains all the data. There is no simple way of deactivating an account, and Google retains all the data. Of course. Google offers a plethora of online services including Gmail (email), Picasa (photo hosting and sharing), Google Plus (social networking), and Google Drive (document hosting). Given that they are all accessed via a single account, their policies as detailed in their support pages, seem to be similar for all. It’s possible to recover a deleted Google account – if you act quickly enough.

The bottom line is that there are no hard-and-fast rules and that each case is taken on merit so there might, indeed, be scope for an authorised person to gain access to the online assets of a dead account holder. However, Google would not respond to our requests for clarification or details. As such, it is not possible to judge, for example, whether all online material is considered equally confidential or whether, for example, Google might grant access to Picasa photo albums but not to more sensitive information such as that contained in Gmail folders.

It’s also pertinent to point out that Google offers an Inactive Account Manager service by which an account holder can opt to have a trusted friend or family member sent an email in the event of their account being inactive for a certain time. The mail contains a link from which particular types of content, as defined by the account holder, can be downloaded.

What happens to your online accounts when you die: Online assets with financial value

As we turn our attention to online property with financial value, the legal situation is much clearer as the Law Society’s Ian Bond explained. “Some assets, for example an online bank account, can be dealt with in the same way as traditionally held assets. Retail websites or gambling sites with an outstanding credit in favour of the deceased are also simple to value and administer in accordance with the law”, he said. You might think that the same applies to property you’ve paid for which is stored on line. Perhaps the most obvious examples are music tracks and books that you’ve bought on iTunes.

We asked Apple how an authorised person can get access to these assets and were told, effectively, that such property dies with the person who bought it. The reason for this is that in paying for a music track, you don’t actually buy the music. Instead you obtain a licence to listen to that music, but the licence is not transferrable. This might sound like a change in policy compared to CDs or LPs but Apple says not. The same applied to music supplied on recordable media, the only difference being that online distribution provides a means by which the conditions of the licence can be enforced. While we can’t disagree with the legal situation, we’d have to say that the onset of online purchasing does seem to have ushered in a new-found determination to enforce that law. After all, we don’t hear a lot about high-profile raids on second-hand record shops and record fairs. The same applies to movies, apps, magazines and books.

What happens to your online accounts when you die: Managing your online property

Any expectation that your online property will become available to your family, or other beneficiary, after your death would be misplaced unless you take precautions beforehand. An obvious solution is to inform your relatives of your various passwords but this isn’t ideal. Most obviously, you might want to avoid any possibility that your online accounts could be accessed while you’re still alive. Even if this isn’t a concern, though, if you have different passwords for each account and you change them regularly – as security experts suggest we should – it would be all too easy to forget to tell your relatives each time you’d changed a password. A solution to the problem of multiple passwords is either to use a password management utility such as KeePass or 1Password, which stores all your passwords in an encrypted file on your PC, or just to list them all in an encrypted Word document, making sure you update the document each time you change a password. Then, depending on whether or not you’re happy for someone to have access to your passwords while you’re still alive, you have two options. Either you give someone the password for your password utility or Word document on your PC, or you provide the information to your solicitor with the instruction to make it available to a named person only in the event of your death.

Dealing with a deceased’s estate can be a lengthy process. This being the case, and bearing in mind that this will be a period of considerable distress, handling a relative’s online property is a job that might not be addressed for some considerable time after their death. A final aspect to consider, therefore, is how long someone can wait before their relative’s accounts, and all their associated data, is deleted due to lack of activity. We reasonably expected that this information would be written into the terms and conditions of each service but apparently this isn’t always the case. While Twitter said that accounts may be deleted after six months of inactivity, neither Facebook nor Google would tell us how long a dormant account will remain active. So, if you’re sorting out the affairs of a loved one who has passed away, don’t wait too long before attending to their online property.

What happens to your online accounts when you die: the law

To understand the legal situation we spoke to solicitor Ian Bond, Partner at Higgs & Sons, and Member of the Law Society’s Wills & Equity Committee who told us that, according to law in England and Wales, “it is the duty of a personal representative to collect and get in the real and personal estate of the deceased and administer it according to law”. “If the deceased had digital assets”, he said, “the personal representatives have a duty to protect those assets and collect them for the beneficiaries”. We’ll see later how this applies to online assets that have some financial value but, to start, we’ll think about online property that has mainly sentimental value. Here, things are rarely as simple as Ian’s initial statement might suggest as he went on to explain. “Digital assets are mostly stored on shared servers; the service providers may be based in a different country from their users, and they may store data on servers in many countries, making it unclear whose laws would apply”. To clarify, he gave an example. “Just because a user dies in London with a Facebook or Twitter account, it doesn’t mean that English law will apply in dealing with those digital assets”, he explained. “In the absence of clarity on which countries’ laws apply, how a digital service-provider deals with an asset following the death of the user becomes a matter for the provider’s terms of use. No uniformity exists so, in reality, each separate digital service provider sits in final judgment when it comes to deciding the fate of the digital assets.” In view of this ambiguous situation, we approached some of the most likely companies that you’ll have entrusted with your online assets. See also: what are my rights when buying tech kit in the UK