Card games tend to be simpler, lighter, cheaper and quicker to play than their board-based cousins, but that doesn’t mean they lack depth or quality: the ones in this article are all strategically rich and beautiful to look at. In truth most board games involve cards of some kind (the superb Cosmic Encounter, Pandemic and Celestia are all based around them) but when putting together this guide we chose to restrict ourselves to ones where cards are the only significant component. A few of these come with tokens to tally scores or money, but that’s it – no pieces moving around a board (no board, for that matter), and no dice. Finally, note that we’ve ignored traditional card games here, simply because they are too immense a subject. But a standard 52-card deck is the most cost-effective purchase of all.

Coup

There’s more than a touch of Poker about Coup, from the starting deal (two cards to each player) to the I-don’t-believe-you-oh-no bluffing/challenging mechanism. It’s super-simple in concept. The deck contains only 15 cards: three each of ambassador, assassin, captain, contessa and duke. On your turn you can take any one action (such as swapping your cards, or assassinating another player), many of which can only be taken if you’ve got a specific card – but you can lie about what you’ve got. Many actions can be blocked by certain cards, and you can lie about that too. The only downside to all this lying is that if you get challenged and caught, you lose one of your two lives. If you get challenged and were telling the truth, your challenger loses a life. And the result is a tense and mind-bending game where you spend half an hour or so climbing inside each other’s heads and driving yourself mad, in a good way.

Love Letter

Love Letter is a pure and nearly perfect ‘small game’. From the simplest of ingredients (21 cards, a handful of counters, the rulebook and a little red bag to store it all in) the makers have created a quick and compelling bluffing game which can be grasped in 10 minutes but keeps revealing new depths for months after. The aim of the game is to end the session with the highest surviving card (the highest of all is the princess, whom everyone is trying to woo) but there are numerous sneaky ways to knock out your opponents before it gets to that point. Brilliant stuff.

Villages

Villages is fantastic fun – a sort of set collecting, rummy-type card game but with masses of aggressive interaction to liven things up. The colour-coded sets you collect and play are villages, made up of little cheery pixellated villagers (such as wizards, knights, farmers and that kind of thing), buildings and domestic animals. Played villages can use various special abilities and will earn points at the end of the round, but they are vulnerable to being attacked, slain, kidnapped etc. You rarely feel safe. The artwork is beautiful; the rules, while a little complex for beginners, are deep and fun and create lots of tension. The only issue is that it’s hard to get hold of a copy of the game, since it isn’t widely on sale – but if you can find one at a reasonable price, grab it right away.

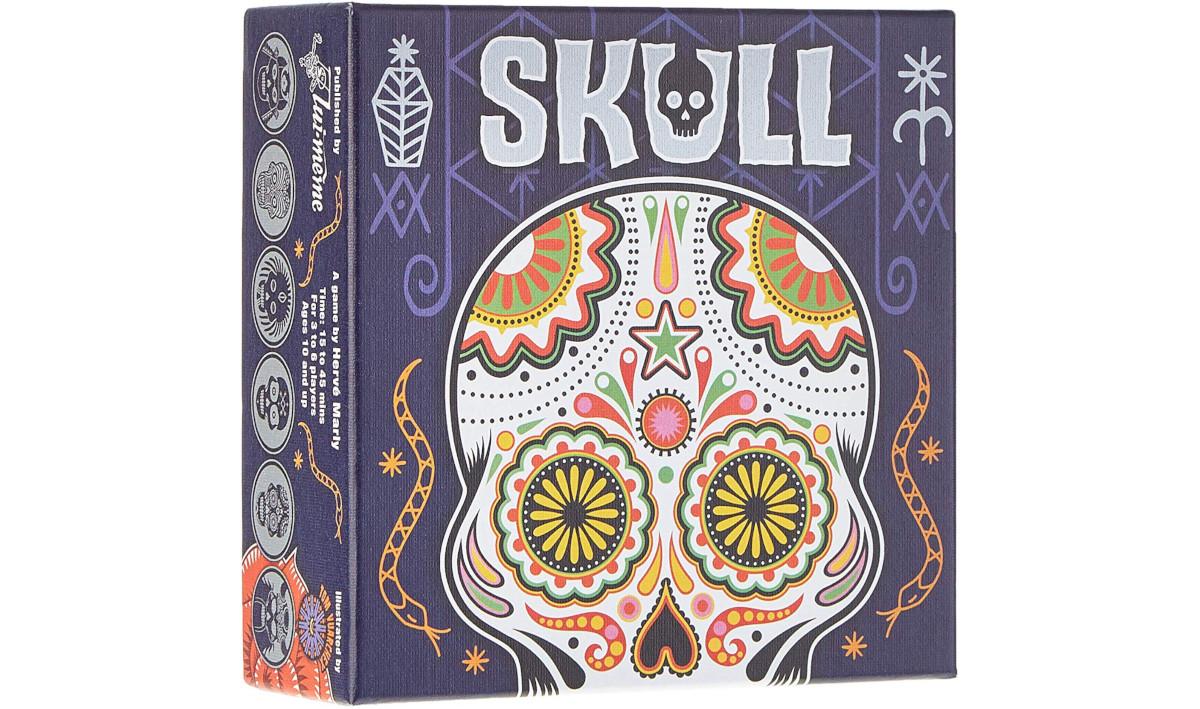

Skull

Mind-bending bluffing game supposedly beloved of biker gangs. You each start with four cards: three roses and a skull (hence the older name, Skull & Roses). You take turns laying these down in the order of your choice, until someone makes a bid – saying they can turn over a certain number of cards (starting with their own) without hitting a skull. Other players can bid higher, or tell them to go for it. Of all the games here, this pub favourite would be the easiest to replicate for free with a handful of beer mats, a marker pen and the rules pdf. We feel that the attractive components are worth the cost, however.

Sushi Go

An antidote to the stressful brain workout of something like Coup, Sushi Go is a gentle collecting game with a touch of strategy to keep things interesting. The (beautifully illustrated) cards each show sushi or related food items: sashimi, wasabi, maki rolls, dumplings and whatnot. You’re dealt a hand of these cards and have to decide which one you want to add to your collection, then pass the rest of the hand to the player on your left. Complication one: the value of each card varies depending on what else is in your and others’ collection. Some items only give you any points at all if they are part of a set, for example; some are competitive – whoever has the most gets the points; and some are never worth points themselves but modify the value of (certain) others. So your decisions call for prediction and risk assessment. Complication two: because of the passing-on of hands and the fact that other players’ collections are visible, canny players quickly build up information about the sort of round it’s going to be: the card types that are rare or common, and the ones that are likely to be snaffled by other players. It’s potentially quite a deep game, really, but there’s still room for players like me who always collect the same thing, and constantly refer to themselves as the “dump-king”. If this takes your fancy but you want something on a grander scale, try Sushi Go Party, which plays up to 8 (standard Sushi Go accommodates up to 5 players) and lets you customise each game from a larger variety of cards.

Lords of Scotland

Across a series of skirmishes, you pick up, play and collect cards depicting fierce Scottish clansmen, and use these to assemble an army. At the end of each skirmish, everybody adds up the numbers in their army (and doubles the score if it’s entirely made up of a single clan) and the winner gets the most victory points. That sounds simple, but Lords of Scotland throws up lots of complications. You can play cards face-down for secrecy, but if you play them face-up you may be able to invoke that clan’s special ability – allowing you to steal other people’s cards, draw extra cards yourself and so on. And often the best option is to deliberately lose an early skirmish where the rewards are less exciting, simply in order to put together a killer hand for later on. This is one of the harder offerings here – we find the terminology a little confusing, so pay careful attention to what everything is called – but we found it highly rewarding once we got the hang of it. Just be prepared for the inevitable First Game Where Nobody Knows What’s Happening.

The Mind

The Mind is a seemingly simple card game where all the complications are created inside your head. You’re working together to play numbered cards in the correct order (whoever has the lowest plays that first, and so on), but you can’t talk to each other. So it’s all about guesswork, and probability, and trying to work out what exactly your wife is trying to convey by that weird face she’s pulling. This is similar in many ways to The Game, which we look at next; we narrowly prefer The Mind, because its level system means you should get at least a few wins before crashing out, but they’re both good.

The Game

In this Google-proof game you’re working together to play all 98 cards on to four piles; two go up from 1 and the others go down from 100. This is harder than it sounds, and while you can’t tell the other players what numbers you’ve got in your hand you can certainly hint at what they should do in increasingly desperate and therefore amusing ways. Be aware that there are several versions knocking around: the one we’ve played dates back to 2015 and is adorned with a skull on the box cover, but a reprint from 2018 (pictured above) is decorated in more tasteful and abstract fashion. You may also find it cheaper, since there’s no English text in the game, to buy a German-language edition and get a PDF of the rules from the internet.

Cards Against Humanity

Cards Against Humanity is not a game you would want to play with younger children, but marketing itself as “a party game for horrible people” is perhaps taking things a step too far. We’d suggest Cards Against Humanity is a game for people who have a wicked sense of humour, and who are not easily offended. There are various rules you can use, but in Cards Against Humanity’s simplest form each player takes 10 white cards (answer cards), picking up another card for each hand they play. You then take it in turns to read out a black card (question cards), starting with the last person to go for a number two (an interesting question in itself). Having heard the question you match what you think is the funniest answer you have to hand, then the ‘Card Czar’ chooses their favourite and it gets an Awesome point. Whoever gets the most points wins the overall game, which can go on for as long as you like. The catch is these aren’t the sort of questions and answers you might hear in pleasant company. When presented with a question such as ‘What’s that smell?’ it’s up to you to judge the temperament of the group and decide whether to select something like ‘Grandma’s knickers’ or ‘A pyramid of severed heads’ as your answer. (We went for a third option in the most recent game we played, but our choice was far too distasteful to publish on Tech Advisor. And yes, we did win the point.) The standard deck costs £20, but you can also buy expansion packs. Should you find the cards too lame it’s worth knowing you can also create your own deck: Cards Against Humanity is available for free under a Creative Commons licence. You can download the rules and blank question and answer cards from the website.

Bohnanza

If you like collecting gold and looking at anthropomorphic drawings of beans, Bohnanza is the game for you. The aim is to plant beans of a single type – chilli bean, dancing bean, coffee bean – in a ‘field’ (ie a row of cards on the table) and then swap them for pieces of gold when it gets numerous enough. The rarer the bean type, the better the exchange rate you’ll get. The problem is that you can only have two fields at once (at the start – it’s possible to buy a third later), and you must play your cards in the order they were dealt. Which means that if you’re unlucky, or plan badly, you could find yourself constantly having to plough up and discard fields of beans that haven’t yet hit the payout point, so that you can free up the area for a new type that you need to play. So it’s partly about thinking ahead, and there’s a surprising amount of depth to this. But it’s also about convincing the other players to make an exchange at a key moment, which is often the only way to avoid disaster.